It may sound counterintuitive, or even just scary, but there comes a point in every freelancer’s career when they have to – or should – turn down a job. Far from being a bad thing, it is a necessary part of freelancing that will ultimately be better for your career and the clients that you work with. Here are some reasons why:

Not Enough Experience or Not Within Your Expertise

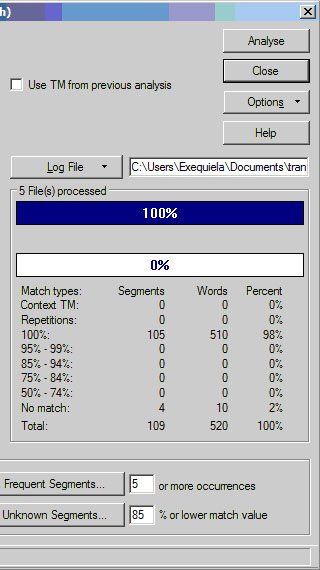

Though a project might sound promising and you might be tempted to gain a new client, you should not take projects that will be very difficult to complete. Consider, for instance, that you are an English to Spanish translator, always translating to your native language Spanish. You receive a Spanish to English project and are tempted to accept it, even though you know that you don´t have the right experience. Or maybe you receive a medical translation when your specialization is law. Once the excitement and sense of calm from getting new work wears off, you’ll be stuck trying to hurry through and complete a translation that takes too long because it is outside of your expertise.

Client Has a Tight Deadline

This might be a client that contacts you suddenly for a rush project, or who claims that every job is “urgent”, or who calls you on Thanksgiving day, or on Sunday afternoon, etc. There are plenty of these clients out there, and they should be avoided (unless you really enjoy being at someone’s beck and call and having no life or freedom, or unless they are willing to pay an extra charge.) You might have the patience to get through one or two jobs with this type of client, but beware when that patience runs out and you’re both stuck with a deteriorating situation.

Money Matters

All clients want to save money, it’s just a part of business. But freelancers should be wary of those who ask for big discounts. It could indicate that the client will not value your work, but it also has a negative impact on your business as a translator. Taking low-priced jobs means that you would need to accept more jobs. And that can make you more stressed about finishing projects quickly, and consequently lead to lower quality in the work that you do. Ultimately, charging a higher rate (not abusive, but a reasonable rate) is better for both the client and the translator.

In addition, projects with payment terms that are far from what is acceptable for you should be avoided. This point is particularly important because when working as a freelancer, you have to make sure that you are creating a cash flow that is sufficient to cover your living expenses. If a project does not include payment terms that would allow you to do that, it is best to pass on the project.

Research the Client for Red Flags

With so many online resources for checking up on a client’s profile or reputation, it just makes sense to do it. A good practice is to always search for a new client on Google and to also look them up on a site like the Better Business Bureau for US and Canada (http://www.bbb.org/). If you are working for a translation agency, a good place to see the agency reputation is http://www.proz.com/blueboard.

While you can’t necessarily believe everything you read online, if you Google a client and several sites with complaints about them come up, it’s a pretty good indication of what you can expect from working with them. The kinds of information you may find online include whether they pay on time, if they are easy to work with, and any specific issues that tend to come up in their business relationships.

Uninformed Clients That Are Not Willing to Learn

Beyond the deadline issue, some clients are just pushy and make unrealistic requests for projects. For instance, they ask 100,000 words translated in a couple of days, and aren’t willing to learn what translation is about (and why that request is not realistic.) A savvy translator will not spend too much energy on these clients. Rather than getting frustrated with uninformed expectations, you can explain politely why the project is unrealistic or tell them that it is not the way you work. If they wish to work with you, they can alter the request.

Follow Your Instinct

A final note is to watch out for clients that just seem too eager to hire you and pay you right away without getting basic information. There are new scams created every day, and experience in picking them out can protect you from falling prey. But even if you don’t have so much experience under your belt in dealing with clients as a freelancer, you can always fall back on your gut instinct. This also goes for projects that are not necessarily “scams” but that just don’t seem right for you, your schedule, or your expertise.

There are many reasons why a project might not be right for you, and it’s in your best interest to know what a “right” project looks like.