Among the challenges facing Spanish language learners is that of learning to pronounce words with letters whose pronunciations in Spanish differ from those in English. Some of these differences are well-known, and many learners begin their first lessons already aware that the Spanish “j” sounds somewhat like the English “h” and that the pronunciation of the “ll” in many dialects is similar to that of the English “y”. Nevertheless, one of the differences often either ignored or poorly understood is the difference between the Spanish “v” and “b” and the English “v” and “b”.

This lack of knowledge or confusion is easily understood: it dates back as far as the Middle Ages, when Spanish scholar Antonio de Nebrija (who believed that grammar was the foundation of all science) applied the Latin pronunciation of these letters (he, like many of his contemporary scholars, believed Latin to be superior to all other languages) to Spanish and published these as rules in his seminal work Gramática de la lengua castellana published in 1492. Nebrija believed that “we must pronounce as we write, an write as we pronounce.” Though this differentiation in the pronunciation of the two letters was rejected by the Real Academia Española in its 1726 edition of the Diccionario de autoridades and its 1741 edition of Ortografía, however, its 1754 version of this latter book recommended pronouncing the “b” as a bilabial stop and the “v” as a bilabial occlusive and this recommendation remained unchanged until the version published in 1911. At the same time, the Academy encouraged differentiating the pronunciation of the two letters in schools in order to make spelling easier. Even today, many elementary school teachers – and some teachers at higher levels – distinguish between the two letters for the same reason. As a result, many native Spanish speakers adamantly defend the differentiation of the two letters.

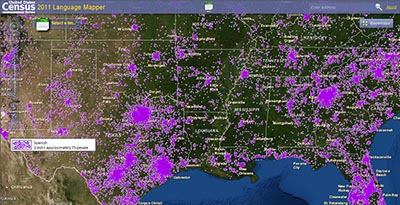

Nevertheless, this Latinizing differentiation is artificial and does not represent the actual pronunciation of Castilian at any period of time. In fact, Tomás Navarro Tomás, a Spanish writer and linguist writing in the early 20th century, stated that this feature probably existed in Hispanic Latin (which developed in the 3rd to 1st centuries BC), as there are written accounts of Hispanic Latin speakers in Rome being mocked for their inability to distinguish between the Latin words “vivere” and “bibere”. In other words, even the substrate of modern Spanish lacked the distinction between the two letters. There do exist some geographical areas where speakers distinguish between the two; this is the result of the influence of contiguous languages (for example, Catalonian) or local languages (this is especially prevalent in some parts of Mexico) where this phonemic distinction exists or existed.

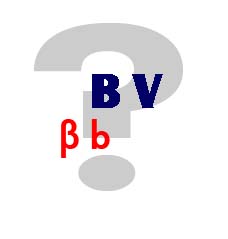

Another root of the confusion about the pronunciation of the “b” and the “v” is the fact that these two letters actually do represent two distinctly different sounds: the [b] (a voiced bilabial stop) and the [β] (a voiced bilabial fricative). This latter sound is often interpreted by English speakers (and speakers of other languages where the b and v represent different sounds) as [v], a voiced labiodental fricative. This sound does not – nor has it ever – occurred naturally in the Spanish language.

What then is the rule for pronouncing these two letters correctly in Spanish?

The rule is actually quite simple and depends on both the position of the letter and the letter or sound that precedes it:

Both “b” and “v” are pronounced as [b] whenever they occur at the beginning of a vocalization of words such as, for example, a sentence: “Bueno” ([bweno]) or “Voy” [boi] or after a bilabial sound (such as [m]): “embestir” ([embestir]) or “invertir” ([imbertir] – the [n] becomes [m] due to the bilabial nature of the [b]).

In all other positions, these two letters represent the voiced bilabial fricative sound represented by [β]. This means that both “tubo” and “tuvo” are pronounced exactly alike: [tuβo].

Following are some examples of how the rule works:

bebe [beβe]

él bebe [el βeβe]

vive [biβe]

él vive [el βiβe]

ambas [ambas]

alba [alβa]

We’re interested in knowing what your experiences with the pronunciation of “b” and “v” have been. Do you pronounce them differently? Tell us about what you were taught in school or how people in your community pronounce them.