For as long as language has existed, it has changed, morphed, and warped as the world and people’s references around them have changed. It is no surprise that, with changing references and realities symbolized by new generations, the youth of each generation changes language and makes it their own. Language, of course, is for communication and in this world that is more open than ever, where people can communicate their ideas and observations easier than ever before, it has adapted to reflect that.

Language Inevitably Changes

While linguistic change is certain, another thing that’s never too far behind it is people complaining about these changes, be they speakers of Japanese, Welsh, or English. Despite the calls of some that millennial innovation in the English language is nonsensical or even something for ridicule, the fact remains that formal written English is relatively unchanged from a couple of centuries ago, which is why readers can still enjoy Dickens a lot easier than they can Chaucer or Beowulf. It is slang that most often changes, and written slang is now more visible than ever before.

New Slang

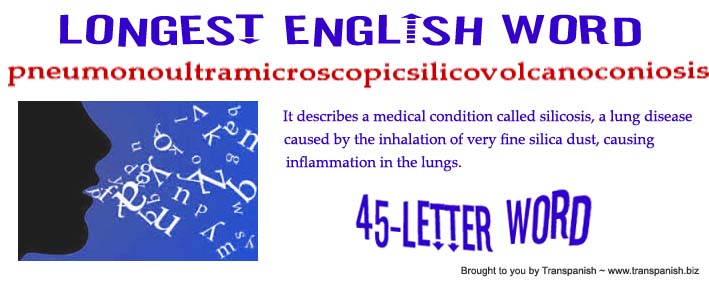

So what changes are we seeing in the English language with the millennial generation? The changes that are most often referenced are the introduction of slang words and phrases. These include the now widespread use in English of terms like “woke” (meaning socially aware), “lit” (meaning fun) and “low key” (meaning subtle), all English words now given different meanings. However, these changes are really just slang, not any radical change to the language, and by the time that I’ve finished writing this article, they may well have become dated. For every slang word like “cool” and “ogle” that enters the English vernacular, there’s many like “radical” or “tubular” that don’t and fall by the wayside becoming painfully dated.

The Impact of Social Media

While there are indeed many unremarkable words like “thirsty” (meaning desperate) and “shook” (meaning shaken) that have become commonplace, what’s different about millennial slang is the development of terms related to social media. As technology develops and becomes the mainstream, language evolves alongside it to reflect people’s interactions with it. An earlier example of this is the introduction of the word “spam” to refer to unwanted emails, now an everyday term. Considering this, it’s no surprise that phrases reflecting the modern online world have become popular. Good examples of this include people simply stating “RT”, meaning retweet in reference to Twitter, discussions over people “trolling” others (meaning to deliberately provoke someone online, although it’s also now used offline) and even discussions over “snap traps” (meaning sending a Snapchat to someone you suspect is screening your messages to see if they open it, thus falling into your “trap”).

Innovation Beyond Words

It’s not just the words that are changing in meaning, but punctuation too. Arguably. The. Most. Noticeable. Example. Of. This. Is. Typing. Like. This. For. Emphasis (as if someone is saying it with great certainty). Question marks and exclamation marks are also sometimes used on their own in messages to indicate confusion or surprise, and of course, the hashtag has entered the mainstream and can be used in casual writing to indicate a theme. As people are able to talk more online, they are adapting language to suit their needs and the emergence of style guides relating to this casual style of writing have emerged. One example of this is Buzzfeed, who state that emojis should appear before periods. In fact, the Netflix comedy series American Vandal jokingly highlighted how strange it was for people to use them after periods, reflecting the introduction of punctuation norms for novel English language concepts.

In short, standard English hasn’t really much changed outside of the widespread preference for gender-neutral language and an increasing lack of fussiness over the passive voice. However, aside from an unsurprising introduction of new slang terms, what we are seeing is the emergence and flourishing of the online environment and the use of language to reflect it.