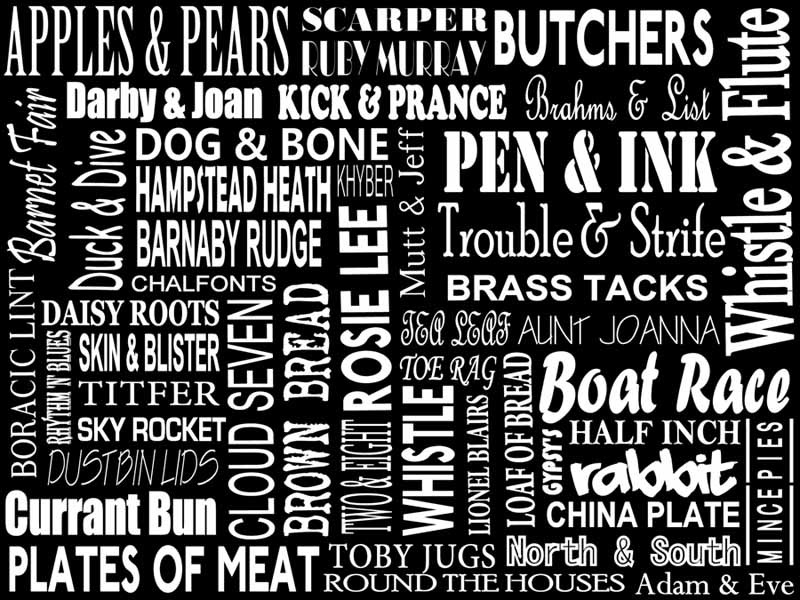

Argentine Spanish, or “Castellano,” differs to the more “neutral” forms of Spanish, found in Bolivia or Perú for example, in that it incorporates a distinctive kind of verb conjugation in the second person singular. It’s also crammed to the brim with phrases taken from “Lunfardo;” a dialect developed by working class Porteños (natives to Buenos Aires) so that they could communicate with each other without the police, and those from richer neighbourhoods, being able to understand.

Many Lunfardo phrases are still used in Buenos Aires today in everyday situations. They continue to form part of the city’s culture, but what phrases are really popular and who tends to use them? A few Argentine women share their favorite Lunfardo expressions of all time…

“La mina que lo amuró”

Put forward by: Renée Martinez, 32, Salta

The verb “amurar” actually means “to tack,” but when placed in the context of this Lunfardo phrase the translation changes completely. “La mina que lo amuró,” means, “The girl who left him.” Did Eduardo Arolas dedicate some of his works to the girl who left him, perhaps? The idea that Arolas pays tribute to “la mina que lo amuró” is debated within a post on Malena Tango. An individual who is “amurado” is, in literal terms, completely isolated from society by prison walls. However, when using the Lunfardo term in a metaphorical sense, someone who is “amurado” is completely head-over-heels in love with another and therefore, “an isolated prisoner of his or her emotions.”

“¡Me pegué un jabón!”

Shared by: Yamila Rosales, 27, Buenos Aires

Even though this phrase when literally translated means, “I hit myself with a bar of soap” (we would need to add the preposition con to the phrase), the Lunfardo expression transmits one of fear and is used when you want to say, “It gave me a terrible fright!” The origins of the expression, and how soap somehow began to be associated with fear, is unclear.

“Si te gusta el durazno, bancate la pelusa.”

Sent to us by: Dafne Schilling, 26, Córdoba

The Lunfardo meaning behind the word “durazno” (which literally translated is “peach” in English) relates to the idea of toughening up or doing something which is difficult. The complete phrase is something relatively similar to “She wants to have her cake and eat it,” in English. It’s a Lunfardo expression used to describe someone who likes doing what they’re doing, but doesn’t really like having to deal with the consequences or the “tough” aspect which is the result of the good stuff that they’re enjoying.

“¡Le dio una biaba!”

Shared by: Marina Manopella, 36, Buenos Aires

“Biaba” is the Lunfardo expression for “golpiza,” which means “to hit someone really hard.” The term is probably of Italian descent and there’s little difference between the “biaba” of 100 years ago and the way in which many young thieves today enter a shop, shouting, hitting and threatening those around them, sometimes even firing a gun and killing someone, without even really knowing why it is they do what they do. “Biaba” is a particularly strong word, with heavy connotations. “Darse la biaba” means “to dye your hair” and it is usually used for men who cover their grey hair. It also means “to take drugs“.

“Me río de Janeiro,”

Selected by: Kiki Chiesa, 34, Buenos Aires

“Me río de Janeiro!” is a Lunfardo expression which might be used to replace the more straightforward Spanish phrase, “me importa un bledo” or “me parece ridículo.” When translated, it’s best to think of the phrase, “Don’t make me laugh!” used in a sarcastic tone by someone who really finds what has been said to them very “un-funny.” The speaker shows little respect and gives very little credit to the person they speak to when they toss out the phrase, “Me río de Janeiro!” The cute factor about the expression is that it’s also a beautiful play on words with the major Brazilian city, Río de Janeiro.

“Ratero oportunista”

Contributed by: Daniela Almirón, 23, Buenos Aires

“Ratero” is a Lunfardo term for “thief,” but the phrase “Ratero oportunista” isn’t one which has to be used literally to refer to a thief. Literally translated to describe a “thieving opportunist,” the phrase is perfect to metaphorically describe someone who is out for all they can get, irrespective of whether or not they ever actually steal something.

”Cana”

Put forward by: Vicky Chiappe, 31, Buenos Aires

“Cana,” which comes from the French word “canne,” is a term that was predominantly used in prisons to describe a policeman’s truncheon. However, there was a time when “cana” was used to mean “police” and then, further on down the line, to indicate or refer to any kind of authority figure.

“Laburo”

Sent to us by: Gabriela Villagra, 37, Buenos Aires

“Laburo” is a Lunfardo word used, in its most basic form, to replace the term “trabajo” meaning “job” or “work.” However, the verb “laburar” can also mean to work hard enough to convince someone of something. For example, “laburar una mina” is a Lunfardo expression which means to “use all possible arguments available to win-over or pick-up a girl.”

“Fe-ca”… café… “Ye-ca”… calle…

Shared by: Mauge Rebuffi, 33, Salta

One particular characteristic of the Lunfardo dialect is the inversion of Spanish words. For example “café” becomes “feca” and “calle” (pronounced “caye”) becomes “yeca.” This simple inversion was one of the easiest ways in which people from the lower classes could disguise their conversations when talking close by to those that they wanted to hide information from.

“Iza de queruza la merluza.”

Contributed by: Alberto, from Lanus in Buenos Aires (honorary male invited to take part…friend of Mauge Rebuffi above)

“Iza de queruza,” is a Lunfardo expression which translates to “Listen up…we’ll do it on the quiet” and “merluza” is a word associated with “drugs.” The phrase is the perfect example of the kind of subjects that the Lunfardo dialect was specially invented to hide.

“¡No seas chanta!”

Natalia Fraga, 32, La Pampa

“¡No seas chanta!” is a Lunfardo phrase you might use when calling someone a liar or when accusing them of scamming you in some way. It can be used playfully to taunt someone or used more aggressively, depending on the tone of voice which accompanies it.