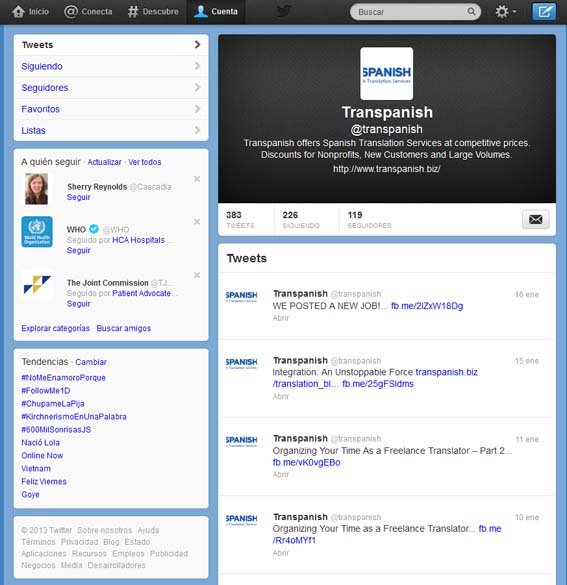

Recent technology has proven useful to language acquisition in many ways. Whether it’s practicing speaking with target language natives via Skype or reviewing vocabulary with one of the myriad smartphone language apps, the various innovations have diversified and streamlined the learning process. For some, though, such technologies have even deeper potential.

Screenshots of The Ma! Iwaidja app, an initiative of the Minjilang Endangered Languages Publication project.

Many Native American tribes, in response to the potential extinction of their native language/s, have begun to embrace apps, iPads, and other related tools in efforts to above all generate interest in younger generations. Currently, there are over 200 Native American languages spoken in the U.S. and Canada, although in many cases they are only spoken by a handful of people. There are an additional 100 Native languages that are already extinct.

The majority of tribes have historically made efforts to pass native languages down to younger generations, but the success of these efforts has waned with time. One of the main reasons for this, of course, is the ever-rising influence of external influence, including both language and technology. Until recently, tribes’ general response to such influence was commonly (and understandably) marked by resistance and resentment.

Many cite the Native American Languages Act of 1990 as being a crucial turning point in the language struggle, for it provided resources and funding to tribes working to revitalize their native tongues. As a result, technology has been increasingly integrated in the process, a trend that may be seen as a sort of “reclaiming” of an early source of oppression. Furthermore, the new learning methods have changed the very nature of the languages themselves.

The phenomenon is also representative of a larger concern—that is, how languages should adapt to or be adapted to seemingly distinct, non-linguistic innovation. Although many take a conservative view, believing that speakers and writers should try to maintain the specific lexis and grammar of languages—and either reject or are highly selective about linguistic innovation—, the majority see language as an inherently malleable thing, always in a state of flux, including the methods used in teaching and learning.

What do you think? Is there any limits when it comes to linguistic innovation and means of acquisition, or does more variety simply and always make a language more rich?